The life expectancy gap between people living in the West Side of Chicago versus those living downtown is up to 14 years. For some West Side neighborhoods, the average life expectancy is as low as 67 years. These grim statistics are driven by a constellation of root causes related to health and social needs, such as systemic racism and less access to quality health care, education, economic opportunity, and a safe physical environment. For Rush University Medical Center, a not-for-profit, 664-bed academic medical center in Chicago, something had to be done to meet the needs of the city’s most underserved populations, many of whom are homebound. People who are homebound are medically complex but typically only access health care during emergencies, which is both ineffective and high cost.

Intervention

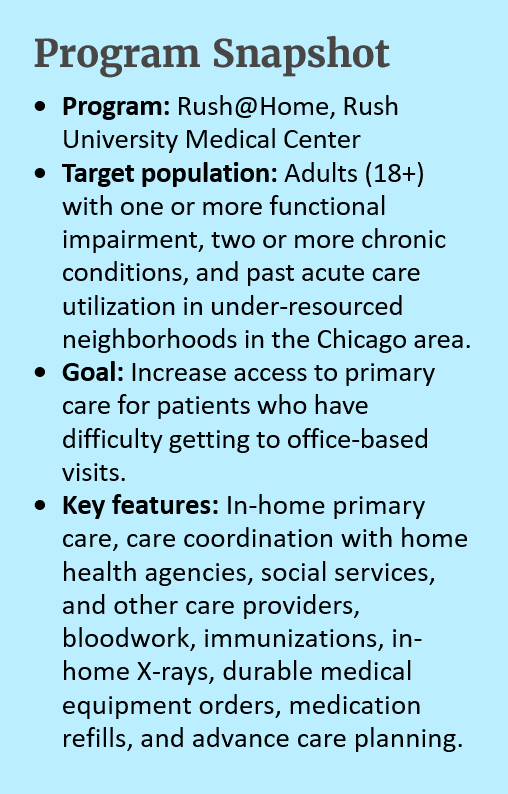

Rush University Medical Center created Rush@Home in November 2018 to bring primary care directly to homebound individuals and those who have difficulty getting to office-based appointments, with the goal of improving health outcomes and reducing acute care costs.

Many adults on the West Side of Chicago are functionally impaired or have multiple chronic conditions at younger ages than in other areas of the city, so Rush@Home serves adults over 18 who meet key eligibility criteria (see Program Snapshot box). It is one of the few house call programs in Chicago that sees patients under 65. As Elizabeth Davis, MD, primary care physician on the Rush@Home care team says: “We couldn’t just focus our program on [age] 65 and over if we're working in neighborhoods where the life expectancy is 69.”

Since its inception, the program has enrolled 187 patients with an average age of 68. Most patients are women and Black. 75 percent are on Medicare, 28 percent are on Medicaid, and seven percent have private insurance.

Implementation

To identify initial patients for the pilot program, the Rush@Home team used electronic medical record data and asked primary care physicians to help identity which of their patients might be good candidates. They accepted referrals from social workers, patient navigators, nurses, case managers, hospitalists, and even patients themselves. The core pilot care team includes a general internist, geriatric physician, and a medical assistant who also serves as a patient navigator.

The Rush@Home team is embedded in a geriatrics practice and a general internal medicine practice, giving patients access to practice-level resources such as nursing and social work support. As needed, they supplement the capacity of the care team by partnering with other Rush resources such as caregiver programs and patient education. They also partner closely with home health agencies for in-home nursing and rehabilitation services. To meet rising demand, the program will soon expand to serve more patients with additional staff, adding a nurse, social worker, four medical assistants/navigators, two nurse practitioners, and an administrative coordinator to the initial pilot staffing model to create a dedicated interdisciplinary care team.

While home visits are currently paid for through fee-for-service, this reimbursement does not cover the costs of providing team-based and home-based primary care to individuals living in homes across a large geographic area. To ensure that the expanded home-based care model will be sustainable, Rush@Home will focus on value-based care models that emphasize high-quality care in the future.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Rush@Home was well-positioned to pivot to serve high-need patients. Early in the pandemic when there were significant access challenges to receive COVID tests, the Rush@Home team started home-based testing. In-home testing enabled patients who tested positive to receive close attention from providers to manage their care, either in home or acute care settings. The program also coordinated an in-home vaccination campaign for enrolled patients and caregivers. Although the neighborhoods that Rush@Home serves have limited pharmacies and other vaccine sites, Rush@Home has achieved high rates of vaccination among both program enrollees and their caregivers.

Impact

Initial analyses of patient health outcomes before and after enrollment in Rush@Home shows reductions in readmission rates, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, length of stay for hospitalizations, and no-show rates. Notably, 95 percent of patients who have died while enrolled in the program did so in the place of their choosing, which is a core metric of success for the Rush@Home team. Further evaluations will help demonstrate how enrollment in the program affects health outcomes and costs of care for program enrollees as compared with a matched control group over time.

Patient stories, like the below example shared by Dr. Davis, illustrate the impact of home-based primary care models:

Insights

Following are lessons from the Rush@Home team that can help inform providers and health systems interested in home-based primary care models:

- Leverage existing resources and identify a provider champion to get a home-based primary care program off the ground. As an academic medical center, Rush@Home piloted the model with the foundation of an existing clinic. The team was able to test out what worked and what did not, which informed the best course of action. The team also noted the significance of having a provider champion. If one provider is interested in and trained to provide home-based primary care, engaging that provider to pilot home visits can be a good starting point.

- Take advantage of technical assistance to help you get started. Rush@Home received valuable technical assistance to develop and expand its program through the Home-Centered Care Institute (HCCI). Rush’s program is also part of a national learning collaborative for home-based primary care.

- Understand and address the social needs of patients. When you visit a patient in their home, you see their world. This makes it easier to uncover social information that may not be gleaned from a clinic visit, such as social isolation, safety concerns, personal hygiene, and food access. The Rush@Home team conducts a comprehensive social work assessment and then refers patients to the appropriate resources to meet their identified needs.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the following Rush University Medical Center staff for participating in an interview to inform this profile: Elizabeth Davis, MD, primary care physician for Rush@Home; Robyn Golden, LCSW, associate vice president of population health and aging; and Nathaniel Powell, program manager of Rush@Home.

In the Field: Spotlight on Complex Care Interventions

This Better Care Playbook profile series spotlights how organizations are implementing evidence-based and promising innovations to improve care for people with complex health and social needs. For organizations seeking to develop or enhance complex care programs, it is valuable to see how peers in the field are rethinking approaches to care. VIEW THE SERIES