By Emma Opthof, Center for Health Care Strategies

In health care, what we measure tells people what we care about. If programs only measure cost, utilization, and narrowly defined clinical outcomes, what truly matters to patients — and staff — may get overlooked. To get to the heart of true quality improvement, the field needs to expand what measures are used to tell stories that reflect real care transformation. As part of the Center for Health Care Strategies’ (CHCS) Advancing Integrated Models (AIM) initiative, eight pilot sites are implementing person-centered care models that integrate care management, physical and behavioral health services, trauma-informed care, and approaches to address health-related social needs. With the help of Joslyn Levy & Associates, an evaluation consultant, the AIM initiative compiled a set of patient- and staff-reported measures to more fully assess the quality and delivery of care within and across pilot sites.

The Better Care Playbook recently spoke with Karla Silverman, MS, RN, CNM, Associate Director for Complex Care Delivery at CHCS, to learn more about the AIM measures and how others in the field can apply them in their own programs.

Q: Why did the AIM initiative undertake this work to define a set of patient- and staff-reported measures?

A: When organizations like the AIM sites make process improvements, they want to be able to measure the impact of the changes they're making. Care model impact is typically measured mainly through cost/utilization and a narrow set of clinically-based outcomes. For someone with diabetes, for example, an outcome measure might show that their diabetes is better controlled, yet they still might be bothered by pain or depression because of their condition. Those are things we may not measure that often get disregarded. As a result, we say we have a positive outcome that looks fine on paper, while the patient feels like their condition hasn’t improved. It's true that whatever we measure, that's where the attention goes.

Additionally, when we look only to reduced costs as our measure of success, it doesn’t bode well because people with complex health and social needs tend to require more care and resources, such as wraparound services and an interdisciplinary care team that can support their health and well-being. The simple truth is that, in many cases, costs are not going down in the short term because more money is needed up front to care for people with complex health and social needs — but this will lead to better care and outcomes in the long term.

Q: Why did you include measures on staff perspectives of care in addition to patient perspectives?

These measures were primarily intended to be used as a tool for quality improvement. In addition to using these measures to provide feedback for the practitioners and their leadership about how patients felt about care being delivered differently, they can also be used to understand what impact new care models had on staff. We really believe that if you don't pay attention to the staff who are caring for people with complex health and social needs, that may ultimately harm patients. A trauma-informed approach is in part about acknowledging trauma that patients have experienced and trying to make the experience of receiving care not traumatic for them, but it's also about provider organizations caring about staff well-being. Many staff who care for patients with complex health and social needs are hearing and seeing some very intense things day in and day out, which can cause burnout and high rates of turnover. The development of measures that ask about staff well-being highlights that this is an important area for provider organizations to focus on.

Q: How did you decide on measure domains? What are some example measures?

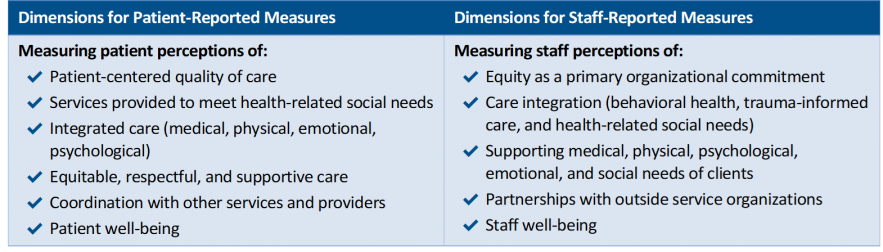

Measure domains for the AIM Measures Library. See brief for more information.

With help from our evaluation consultant and evaluation advisory committee, and informed by research on the current state of complex care measurement, we identified potential opportunities for increasing the use of staff- and patient-reported measures. Our measures are not intended to replace other complex care measures, but are complementary and fill in gaps in the field with the goal of helping people with complex health and social needs to improve their health and well-being.

For example, on equity: Do patients feel understood, trusted, and respected? Do they feel like there are other people who look like them at the organization? To drive health equity, we want patients to be engaged and feel welcome and listened to in the places they receive care. But if we don’t assess how we are doing in this area, we can’t impact this. Similarly, do staff feel like their organization supports equitable care and reducing disparities? It builds on the premise that it's important for staff to believe that they are part of an organization that is committed to promoting health equity.

Another measurement domain identified is care coordination. Do patients feel like their care is coordinated when you explain that term to them? Do they feel like their doctors are talking to each other? So many of us have had that experience where someone calls and you're like, well, someone just called me about that and they are clearly not talking to each other, which can be very overwhelming. Do staff also feel like departments and providers communicate well with each other about what is happening with patients?

Well-being is another area that we believe is a critical part of how we define a good outcome. Going back to the diabetes example, a patient’s A1C lab work may look okay. But if they have numbness in their hands and they feel depressed, then the patient might feel like they’re not getting good care. Or maybe the care they are getting is fine but it’s not enough. These measures help provider organizations and payers receive valuable feedback about where extra attention and focus is needed. That’s why a well-being approach and a focus on what patients feel is important.

Q: What are some considerations for other sites that may want to use these measures?

If you're going to ask staff to survey patients about their care experience, it's important to set that up in a way that is thoughtful to both patients and staff. Program coordinators should think about any training staff will need if they are asking patients these survey questions, what language will be used, the method of collecting information, and how and why it is being collected. It’s good to have a plan for what programs will do with this information and clearly communicate this to both patients and staff. It’s also important to consider how the data will be shared back with patients. Those who answered the questions may be interested in the results and those who didn’t participate may also be interested. But if the measures are used and patients don’t know what for, what the results were, or if the results had any impact on the organization, it could feel disrespectful of everyone’s time, and potentially intrusive for patients.

I would also encourage organizations to not think they have to use all these measures, nor do they need to reinvent the wheel by creating a new process from scratch. It could be helpful to incorporate a few of these measures into existing quality improvement methods and see what information can be collected to refine approaches to care models.

Q: What do you think are next steps for measurement in the field of complex care?

The complex care field needs to have more conversations where we connect what we know are the drivers of complex health and social needs with strategies that can mitigate those drivers. Payers and larger health systems, particularly those who care for a large portion of people and communities who are covered by Medicaid, should commit to measuring how trauma-informed an organization is or their practices are, or how accessible and integrated behavioral health services are.

We also need to track how well an organization does not just at screening for health-related social needs, but whether we are connecting people to resources in a community and the quality of their experiences in getting connected. People with complex health and social needs are often deeply affected by poverty and living in communities that lack resources. In addition, trusting relationships between providers, patients, and the community are essential to high-quality health care, so we should figure out a way to measure trust and relationship-building. Finally, the field needs equity measures that hold payers and providers accountable for reducing health disparities across payer groups, income, and race/ethnicity.